CATEGORIES

- (3) Negotiating Tax Debt and Payment Arrangements with SARS

- (2)Account / Profile

- (547)Accounting

- (2)Accounting and Finance

- (28)Audit

- (156)Auditing and Assurance

- (1)Business

- (1)Business Management

- (3)Business Rescue

- (101)CIPC

- (7)Compliance

- (18)Ethics and Professionalism

- (46)Financial Reporting

- (1)Government Funding Applications

- (4)Guides

- (1)Individuals Tax

- (26)Law

- (37)Legal and Compliance

- (2)Management

- (8)Miscellaneous

- (28)Money Laundering

- (1)Personal & Professional Development

- (2)Practice Management

- (2)Professional Ethics

- (3)Public Sector

- (145)Regulatory Compliance and Legislation

- (41)SARS Issues

- (27)Sustainability Reporting

- (37)Tax

- (1)Tax Update

- (9)Technology

- (1)Wills, Estates & Trusts

- Show All

How the auditors broke capitalism

- 09 July 2019

- Accounting

- Ciaran Ryan

We are programmed to regard accountants with reverence and unquestioning trust. They are the record keepers of the economy and arbiters of financial truth.

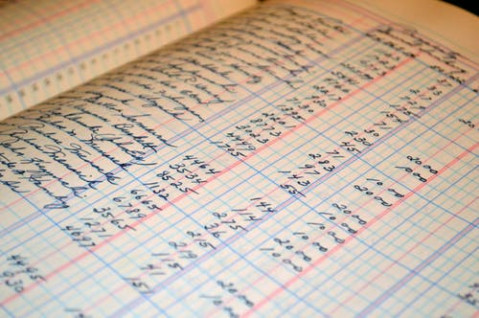

Double entry bookkeeping was an astounding development. It allowed business owners to record assets and liabilities rather than simply track the movement of cash and goods. It introduced the concept of ‘capital’ to the business world, centuries before Karl Marx wrote Das Kapital. With this new insight, business owners could accurately reflect profits, which in turn opened up opportunities for outside investors.

Just as astounding as the development of double-entry bookkeeping is the rise of the Big Four accounting firms – EY, PwC, Deloitte and KPMG – as business titans equal to or even mightier than their clients. The Big Four audit 97% of US public companies, 100% of the UK’s top companies and 80% of Japanese-listed companies. Not to mention their overwhelming representation among the JSE’s top companies. And yet trust in the accounting profession has seldom been lower.

Richard Brooks, author of Bean counters: the triumph of accountants and how they broke capitalism, details why this trust has slipped, and how a nicely balanced set of figures can often be a fraudster’s friend.

The major accounting firms have managed to avoid the scrutiny that their importance warrants. Perhaps, as Brooks advises, we should force them to open their financial statements to public scrutiny so we can see how they earn their money.

Before the Big Four there were the Big Five – Arthur Andersen & Co having disappeared in a puff of smoke after it cooked up false accounts for the now-defunct US energy company Enron.

A mandatory 10-year audit rotation is the latest solution to this overwhelming concentration and the inevitable Stockholm syndrome that comes from having auditors sleep with the same client, year after year. Consider that KPMG counted General Electric as a 106-year-old client and PwC stepped down from the Barclays audit in 2016 after 120 years. It hardly needs pointing out that given enough time, the Big Four (if they are still around in 10 years, which is a pretty safe bet) will eventually cycle back to the clients who rotated them out of their engagements.

Accounting regulators are working overtime to keep up with the schemes being hatched to boost revenue (think Tongaat) or hide liabilities (Steinhoff). Given enough accounting scandals, and we surely have enough of those, investors will start to apply a ‘truth discount’ on all public companies’ figures.

It would be foolhardy to count on the regulators bringing sanity to the profession. As Brooks points out, the accounting standard-setters are swimming in alumni from the Big Four, ensuring the rules are crafted to suit the major accounting firms and their clients. If you’re a major company, you cannot stray very far from one of the Big Four, despite the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors’ (IRBA) efforts to transform the sector and introduce co-audits for black firms.

Every crisis is a revenue opportunity

What is astonishing is the growth in revenue for the Big Four firms through good times and bad. Brooks demonstrates that their revenue growth barely paused for breath during the 2008/9 financial collapse. Every crisis, or indeed change, is a revenue opportunity for these firms: Y2K, climate change, cyber security, corporate governance, business restructuring, and integrated reporting. You name it, they have a solution for you. The result is sports-star-level incomes for men and women employing no special talent and taking no personal or entrepreneurial risk.

Worldwide, these firms make just 39% of their income from audit. They have become consulting firms with auditing sidelines. Though these firms will swear that auditing and getting the numbers right is the sacrosanct heart of their business, the evidence suggests otherwise. With so many inadequate audits on their own ledgers, one might expect a dip in their earnings. You would be wrong. Poor performance is not a matter of life and death when there are so few competitors from which to choose.

Their own key performance indicators (KPIs) emphasise revenue growth, profit margin and staff satisfaction, rather than exposing false accounting, fraud, tax evasion and the systemic risk these pose to the economies they operate in.

The demise of sound accounting became a critical cause of the early-twenty-first-century financial crisis, says Bean Counters. The tendency is to blame reckless banking practices for the last financial collapse, but far less attention is given to the accountants who signed off on dud loan books.

Books sanctified by 'magic'

Vincent Daniel was a disaffected former Arthur Andersen accountant employed by Steve Eisman, depicted in the film The Big Short. In just a few months, Daniel came to the conclusion that the subprime mortgage loans being dished out by the major banks suffered exceptionally high delinquency rates. He saw what the major accounting firms had apparently missed or ignored. Eisman and several other short sellers made fortunes predicting the subprime crisis – yet the banks’ books, sanctified by the magic of mark-to-market accounting, pretended nothing was amiss. Millions of people were impoverished by the willful negligence of the accounting firms. That’s what happens when accountants go rogue.

Undeterred, the Big Four raced off to India and China to capitalise on the record-breaking growth in these zones. The Bean Counters details how the same lapses in oversight started to appear in these new markets. Deloitte was forced to resign from two important clients after signing off on vastly inflated profit figures. Again, it was the short-sellers who highlighted these anomalies. PwC was fined by US authorities for a deficient audit at Indian IT company Satyam. In one country after another, each of the Big Four have been sanctioned, fined and worse for turning a blind eye to fraud, corruption or fake accounting.

Despite the economic wreckage caused by accounting firms, they operate with relative impunity. “Even before Enron, the big firms had persuaded governments that litigation against them was an existential threat,” writes Brooks. “They should therefore be allowed to operate with limited liability, suable only to the extent of the modest funds their partners invested in their firms rather than all their personal wealth.”

Perhaps even more troubling is the fact that governments turn to these accountants for advice on tax, finance, trade and other issues.

Complexity is always a money-making opportunity for these accountants, and the rules they craft in the “national interest” are often serving another master entirely. Are these the right people to be guiding national policy?

Blatant corruption in accounting is the exception. The real problem is the profession’s “unique privileges and conflicts that distil ordinary human foibles into less criminal but equally corrosive practice,” says Brooks.

For years there has been talk of breaking up the Big Four, and detaching their audit from their consulting arms. It happened after Enron and is happening now again. The accounting firms concede the need for reform, but never to the point of threatening their fee-earning capacities. One possible solution is to have an independent body appoint auditors, rather than allow clients to make their own choices. After all, auditors are there to perform a public oversight function that goes far beyond the interests of management and shareholders. Audit rotation will certainly help. But the only real long-term solution is to reintroduce a questioning, objective and skeptical mindset to the business of accounting and auditing.

This article originally appeared in Moneyweb.